|

| |

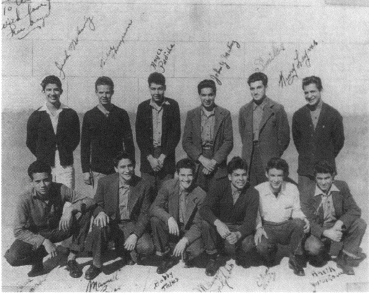

The Sleepy Lagoon Case

Sleepy Lagoon Case

After World War II Chicanos returned home to their

barrios with new hope. The G.I. Bill provided Chicano veterans

with new opportunities for education, job training, and home loans

that were never possible before. Economic competition for semi-skilled

industrial jobs created tensions between Chicanos and whites in the

greater Los Angeles area.

One major event was the "Sleepy Lagoon case." On August 2, 1942, José

Díaz was found unconscious on a rural road near Los Angeles,

apparently the victim of a severe beating. He passed away never regaining

consciousness. His death was a result of a fracture at the base of the

skull. No weapon was found or proof of murder established. Díaz

had participated in a gang rumble the preceding evening at a nearby

swimming hole. As a result 23 Chicanos and 1 Anglo who had participated

in the fighting were charged with murder.

Two of the indicted youths asked for the separate trials and were subsequently

released. The other 22 were tried together on 66 charges. The Judge Charles

W. Fricke made it known of his bias against Mexicans, and the prosecution

repeatedly called attention to the racial aspects of the trial.

Throughout the court proceedings the defendants were denied haircuts

and a change of clothing. They wanted the defendants to resemble the

prosecution's stereotype of the unkempt Mexican.

In January 1943, the jury found 3 of the youths guilty of first-degree

murder, 9 guilty of second-degree murder, and 5 guilty of assault. The

remaining 5 were found not guilty. In October 1944, the California

Distract Court Appeals unanimously reversed the lower court's verdict,

dismissing the charges for lack of evidence.

Even though the charges were dropped, The Sleepy Lagoon case had

widespread negative repercussions. The Los Angeles papers exploited

the situation by using sensational journalism to emphasize Chicano

crime. The pressure was now on the police to stop this so called

"crime wave." The police reacted with systematic roundups of Chicano

teenagers. This included police harassment of Chicano youth clubs,

arrests based on race and mere suspicion, and over policing

of Chicanos barrios. It got to the point where Washington put

pressure on the newspapers to stop using the word "Mexican"

in crime stories. The papers replaced it with nonspecific but

negative racial epithets of "Pachucos" and "Zoot suiters".

|

|

|

|